Specialdocs Featured in Popular Boston-Area Publication

The benefits and growing mainstream appeal of concierge medicine were recently explored in the prestigious Massachusetts consumer publication, Wellesley-Weston Magazine, featuring interviews with Specialdocs and our physician-clients. Writer Keri Bancroft shared compelling answers in her article titled “Concierge Medicine: Is it Right for You?” with insights from Specialdocs CEO Terry Bauer, Special Docs Alan Glaser, MD and Alyson Kelley-Hedgepeth, MD, highlighted below.

Concierge doctors have been around since the late ’90s. At first, having one was considered an option only for the super-rich, since these practices had retainers that were astronomical. But over the years that has changed as concierge medicine has become more affordable and mainstream. Demand has also increased during the past year as people look for reassurance and more personalized care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It’s vital to go well beyond a patient’s immediate symptoms and consider every psychological, social, & emotional factor underlying the condition. In my new practice, there is time for patients to share their whole story, which allows us to explore the root cause of their illness. Only then can the real healing process begin. -Dr. Alan Glaser of Wellesley Primary Care Medicine

Specialdocs CEO Terry Bauer explained that for doctors, the concierge model lets them “focus on the art of medicine, not cranking patients through.” Additionally, concierge doctors are not beholden to the payers but to the patients, don’t go home exhausted, have more time to study and learn to be better physicians, and may earn more money. Concierge medicine has also become more available to a larger segment of patients. Dr. Alyson Kelley-Hedgepeth, a concierge cardiologist in the Lown Cardiovascular Group in Chestnut Hill, notes that the cost of concierge medicine has gone down so much that it is now equivalent to going out to eat a couple times a month.

Terry Bauer also detailed the value of membership in a concierge medicine practice for patients: “A concierge agreement pays for ‘noncovered services,’ which means you pay for your concierge physician to dramatically limit his or her number of patients to ensure direct availability and adequate time for each patient,” said Bauer. “This means same-day appointments, significantly longer and comprehensive appointments, and having your physician’s personal cell phone number.” He noted that during the pandemic, concierge practices across the country experienced an increase in patient enrollments as more people sought reassuring, personalized care.

Concierge medicine is becoming more affordable and more mainstream. Not only does it benefit the patient, but the doctor too. Doctors with a concierge practice can practice their vision of medicine. They are not beholden to an insurance company, but to their patients. Doctors don’t go home exhausted and have more time to study and become better physicians. And for patients, the biggest benefit is a doctor who knows them and spends time with them when they need it the most. Concierge medicine is the quality health care both patients and doctors deserve.

Read the entire article here and discover why concierge medicine benefits everyone.

The post Specialdocs Featured in Popular Boston-Area Publication appeared first on Specialdocs Consultants.

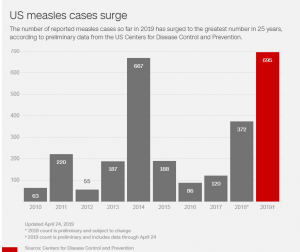

What are the newest guidelines for measles vaccinations?

What are the newest guidelines for measles vaccinations?

Please explain the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)’s revised definition of evidence of immunity to measles, rubella, and mumps.

Please explain the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)’s revised definition of evidence of immunity to measles, rubella, and mumps.